Lighting Design In Depth: Magic Sheets

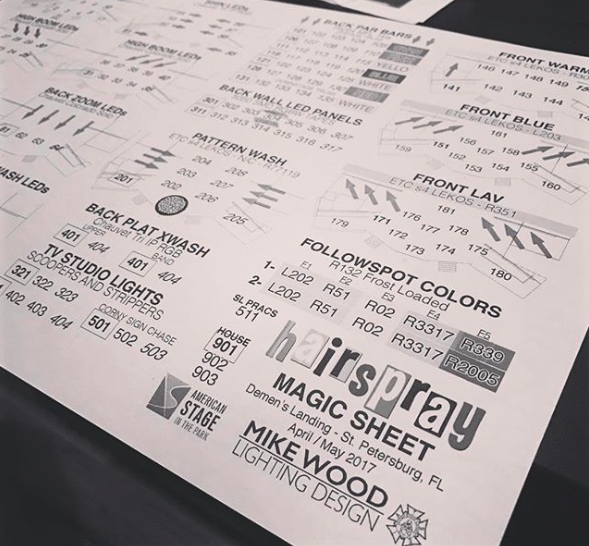

This week, award-winning theatrical Lighting Designer Mike Wood returns to the Lighting Lounge to talk about the importance of Magic Sheets and how they can be extremely helpful on-site. (The article was originally posted on Mike's website here.)

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important pieces of paperwork in theatrical lighting is the magic sheet. It's a single document that simplifies the entire lighting rig down to a page or two, allowing the designer to quickly find and recall channels and groups during programming and tech.

This article is about the paper versions of magic sheets - not the EOS versions.

There are many different ways to make a magic sheet and many different visual styles - the thing about magic sheets is that there really are no "standard" layouts or rules like there are with some other lighting documentation. The magic sheet really just has to be useful to the designer.

Throughout this post, I'll be referring to my process and my way of doing things - remember that this is just my approach and that everyone you talk to will have a different method or opinion - and that's okay! Take the things that work for you, and leave the things that don't.

WHAT IS A MAGIC SHEET?

Simply put, a magic sheet is a document containing a simplified visual representation of the lighting rig as a whole, typically divided by systems of light.

Simply put, a magic sheet is a document containing a simplified visual representation of the lighting rig as a whole, typically divided by systems of light.

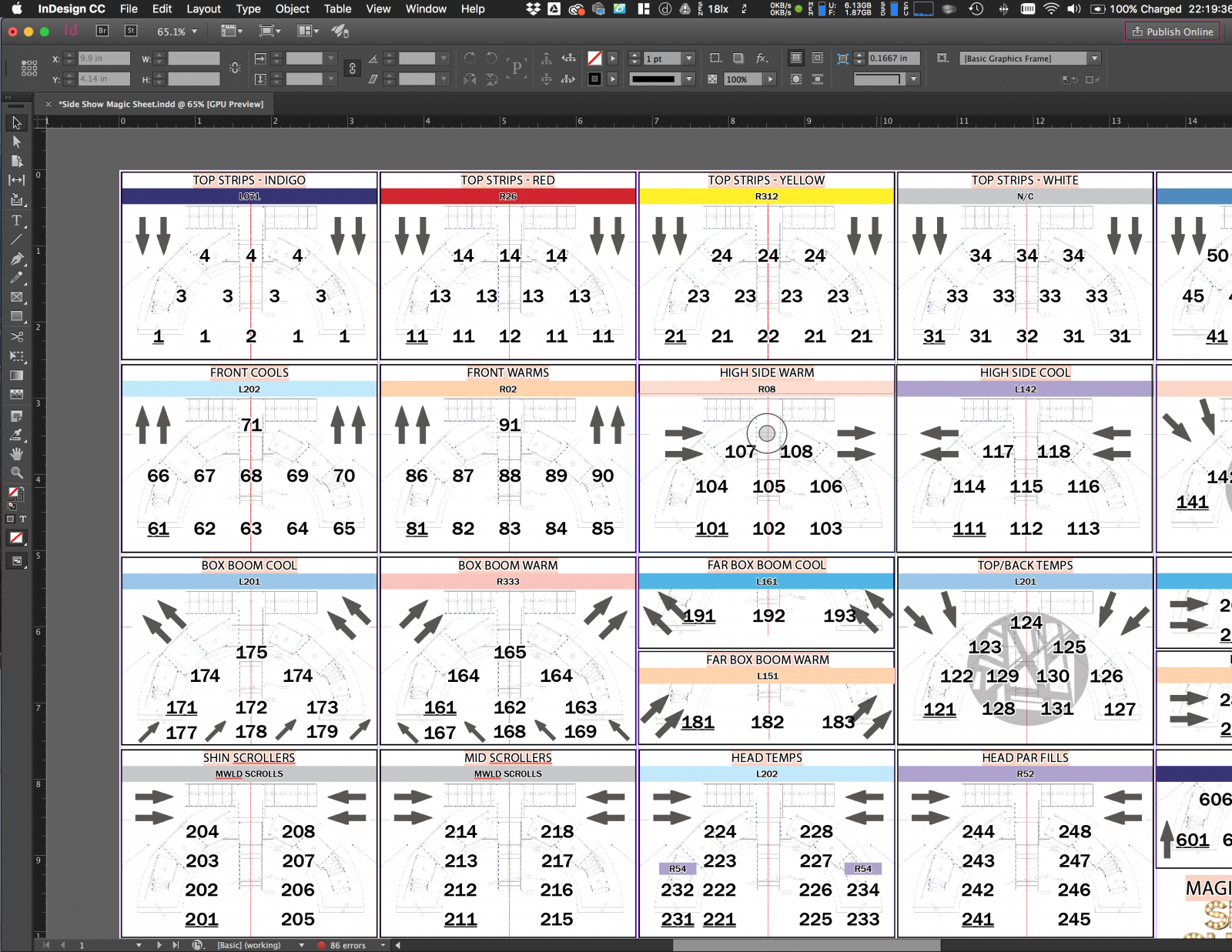

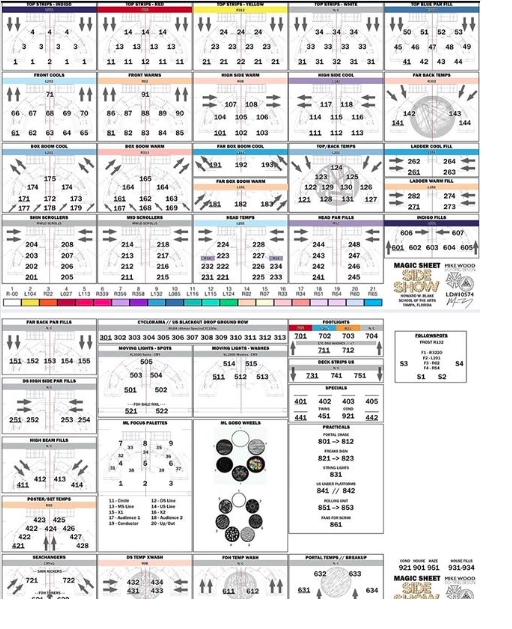

(Left) The magic sheet for a production of Side Show at HWB School of the Arts in Tampa Florida, which my team and I lit in 2017.

Each little box is an individual lighting system with a top-down view of the stage. The channel numbers are superimposed over the part of the stage that the beams will hit. I also include a color bar with a rough approximation of the gel color, as well as direction arrows.

The direction arrows and the color bars help with finding systems of light quickly during tech. I also arrange similar systems in the same row or column of the sheet. For instance, in the Side Show example on the left, all of the top systems are across the very top of the page. The front and high side systems below that, then box booms, then side lights.

WHY NOT USE THE LIGHTING PLOT?

When I teach about magic sheets, this is typically the first question that gets asked. "Why not just use the light plot? All of the lights are already on it, why create this extra document?"

Well, a few reasons. First, typically light plots are very large pieces of paper. The smallest ones I typically print are still 24″ x 36″ - manipulating a page that large at the tech table would be distracting for everyone in the room - and I'd spend more time fumbling with the paper just to find the channels I wanted.

Even with a digital light plot, I'd be zooming all around and trying to find the information I need in between a whole bunch of information that I don't.

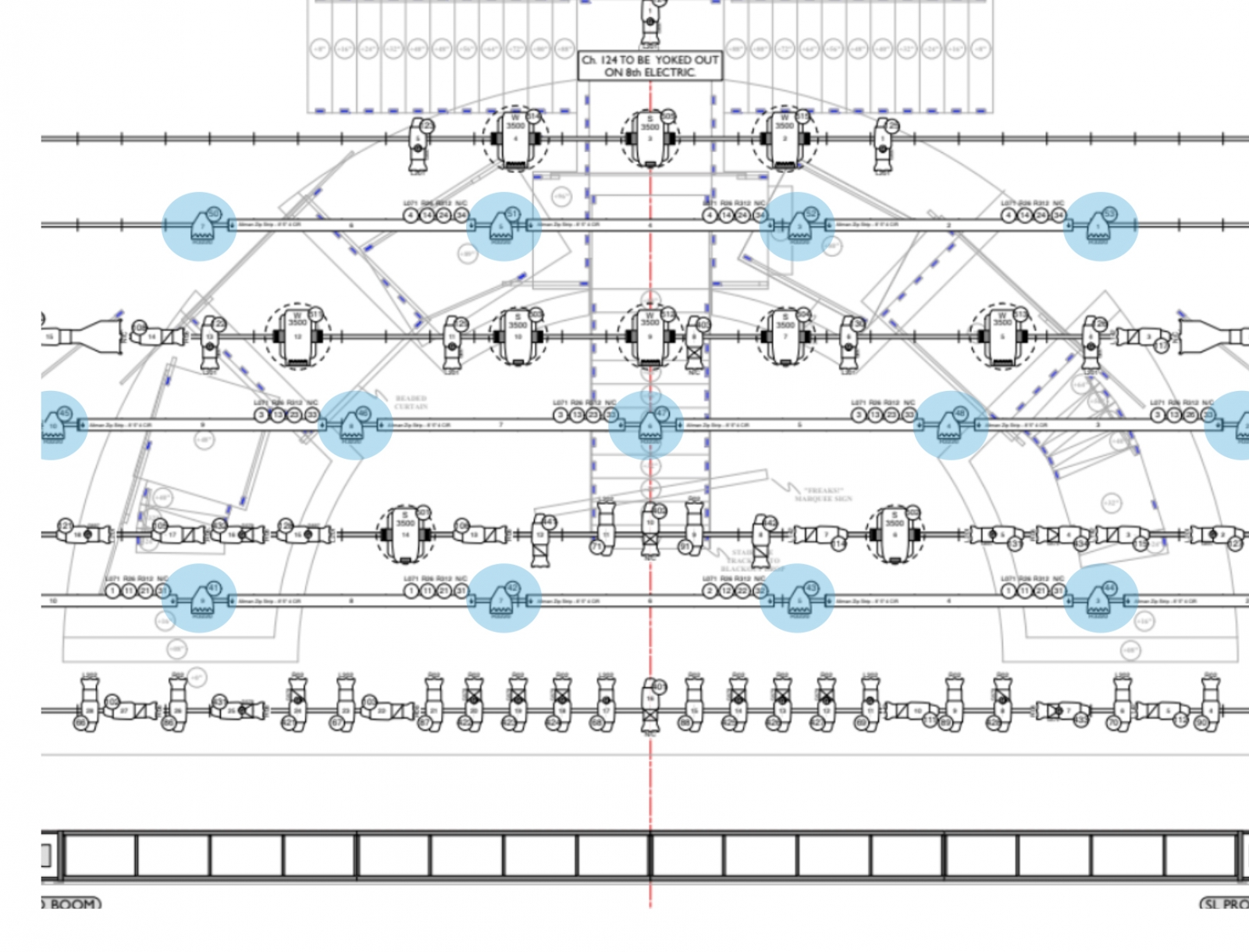

Let's use Side Show as an example again - pictured above is a couple of pages from the lighting plot. The show was large enough that the data needed to be separated into multiple drawings; One for overhead, one for FOH, one for booms and deck instruments… and another for all of the scenic practicals. Imagine trying to quickly find something when hunting through all of those pages at once…

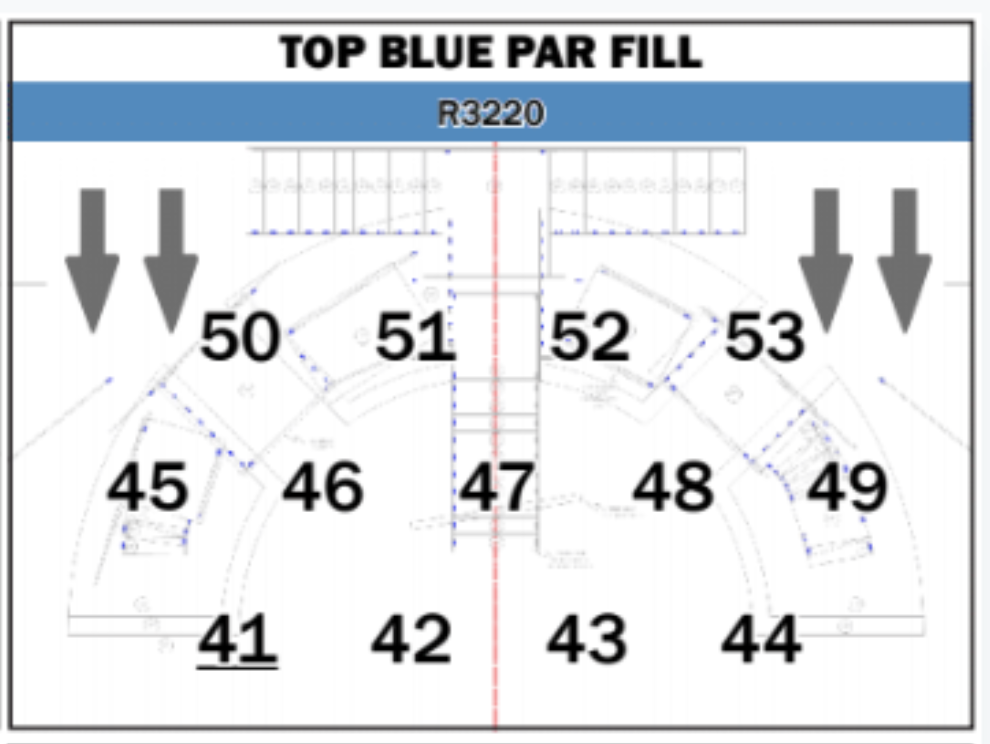

For instance - let's try to quickly find the top blue par fills in the overhead plot. (They're highlighted in the image right) Now that we've found them, find their channel numbers. How long would that take? Too long, when you're trying to write 500 cues.

For instance - let's try to quickly find the top blue par fills in the overhead plot. (They're highlighted in the image right) Now that we've found them, find their channel numbers. How long would that take? Too long, when you're trying to write 500 cues.

Now, multiply that frustration for each system of light that you use in your show. See why it might be beneficial to simplify?

See? Much easier to read. I know by looking at this that if I wanted a center pool of R3220 blue light, I would choose channel #47.

CREATING THE MAGIC SHEET

My magic sheets are typically the last piece of paperwork that is generated before I focus a show. They're also exclusively the one piece of paperwork that I always make myself and never outsource to an associate or an assistant. I typically make them a few days before focus. Creating them myself allows me to become very familiar with the rig and helps me visualize what I'll do at the focus call. Sometimes, the plot and other paperwork have been done for a month or more and I've done other shows in the meantime - taking time to make the magic sheet gets me in the zone for that particular show. Every once and a while, it also exposes problems - but that's another story.

The first thing I do is print a cheat sheet from the Paperwork Management Portal, which shows me the bare amount of information needed to create the sheet. Channel, color, gobo, and purpose.

The cheat sheet doesn't really help me know what light is going where, but it does give me a checklist of instruments in channel order that I can reference to make sure I've included every instrument. I typically print this document out and have a highlighter at the ready to check them off as I go. (Click the photo to view the cheat sheet PDF.)

The cheat sheet doesn't really help me know what light is going where, but it does give me a checklist of instruments in channel order that I can reference to make sure I've included every instrument. I typically print this document out and have a highlighter at the ready to check them off as I go. (Click the photo to view the cheat sheet PDF.)

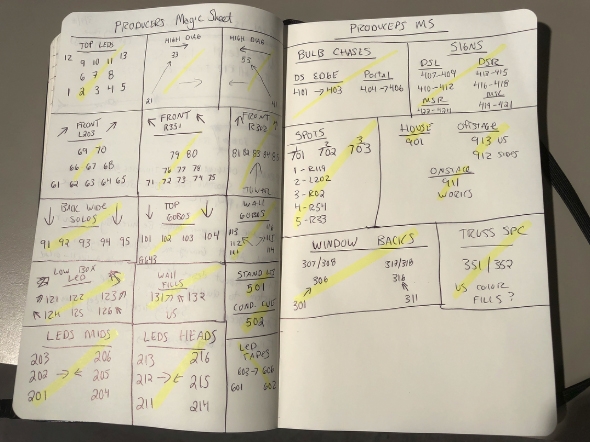

I then make a handwritten version of the magic sheet so that I can get an idea of how many systems I have, as well as how they will lay out on a page. Here's a sample of the hand-drawn version for a recent production of The Producers at American Stage in the Park.

Now it's time to start to turn the handwritten magic sheet into a digital one. The first step is gathering the various graphic assets that I'll need to create the sheet. There's nothing worse than starting and then having to go back and forth to get things. I like being "in the zone" and knocking it all out in one go.

This means that I'll gather images for all of the gobos I'm using, as well as show logos, company logos, and most importantly, a blank image of the ground plan that I can use as a backing image for each system box.

This means that I'll gather images for all of the gobos I'm using, as well as show logos, company logos, and most importantly, a blank image of the ground plan that I can use as a backing image for each system box.

I capture a quick screenshot using the built-in screen grab functions of MacOS.

ADOBE INDESIGN

As some of you are probably aware, I love sharing the work that I'm doing with people. I frequently post not just pictures of my shows and pictures from backstage, but entire paperwork packages for shows. I do this because I love sharing, especially with students, the really cool stuff that I get to do.

Without fail, I always get the same comment on Instagram whenever I post an image of one of my magic sheets - "What do you use to make these?"

The answer is Adobe InDesign. InDesign is used to layout everything from books to newspapers and more. It's designed as a publishing tool, which makes it way more powerful than a word processing program, spreadsheet program, and yes, even Vectorworks. There is a pretty steep learning curve (as there is with any professional software) but once you use it, I promise you won't go back. Especially to Vectorworks… seriously, how do you guys use Vectorworks to create magic sheets?!

The answer is Adobe InDesign. InDesign is used to layout everything from books to newspapers and more. It's designed as a publishing tool, which makes it way more powerful than a word processing program, spreadsheet program, and yes, even Vectorworks. There is a pretty steep learning curve (as there is with any professional software) but once you use it, I promise you won't go back. Especially to Vectorworks… seriously, how do you guys use Vectorworks to create magic sheets?!

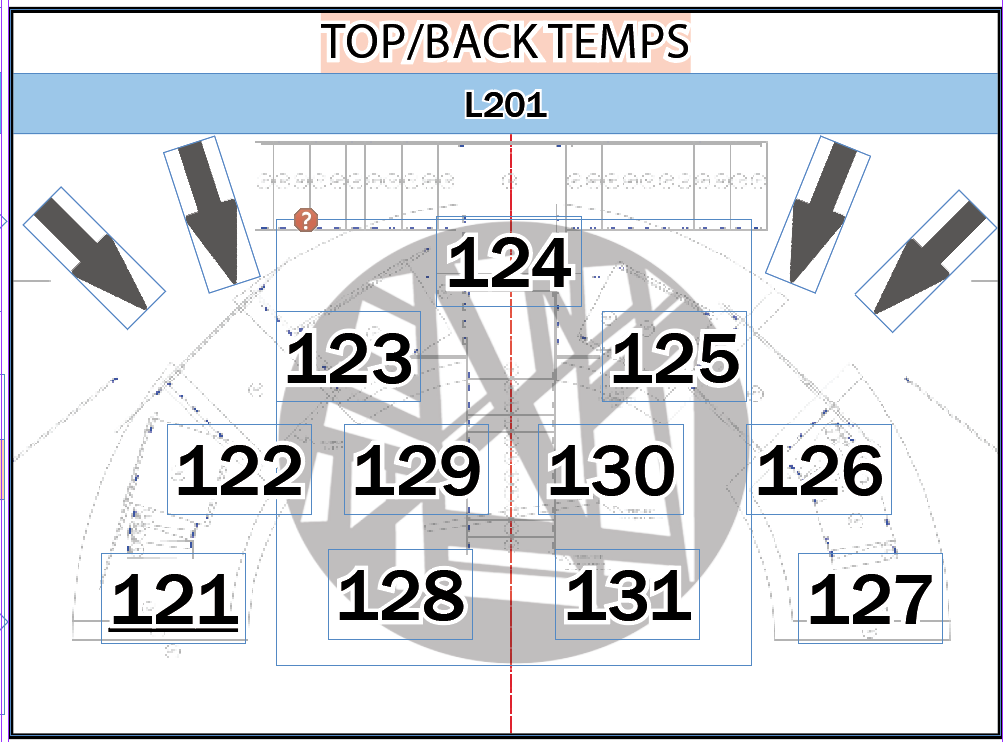

Each box is made up of several layers of items - the base layer is the ground plan image of the set. Sometimes I'll give that some opacity to fade it out a bit, but that really depends on what it looks like. On top of that, there are text boxes for each channel number so that I can move them all around as needed.

Each box is made up of several layers of items - the base layer is the ground plan image of the set. Sometimes I'll give that some opacity to fade it out a bit, but that really depends on what it looks like. On top of that, there are text boxes for each channel number so that I can move them all around as needed.

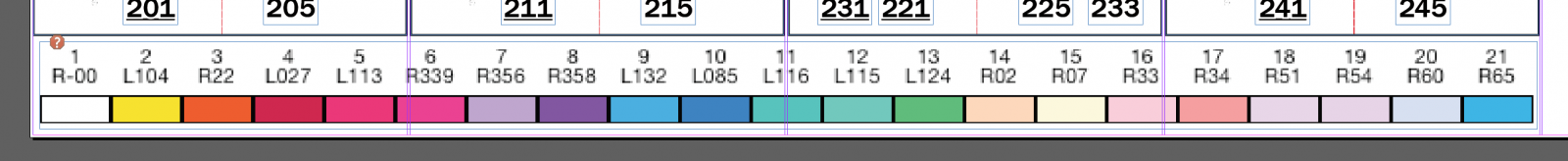

I use a few conventions throughout my magic sheets - group numbers are always indicated by an underlined number within the system. Subgroups are formatted to be in italics.

In the example on the left from The Producers in the Park, we see that group 1 refers to all of the top LEDs (Channels 1 through 13.) Group 5 would only pull up the DS fixtures. Group 8 the MS.

In the example on the left from The Producers in the Park, we see that group 1 refers to all of the top LEDs (Channels 1 through 13.) Group 5 would only pull up the DS fixtures. Group 8 the MS.

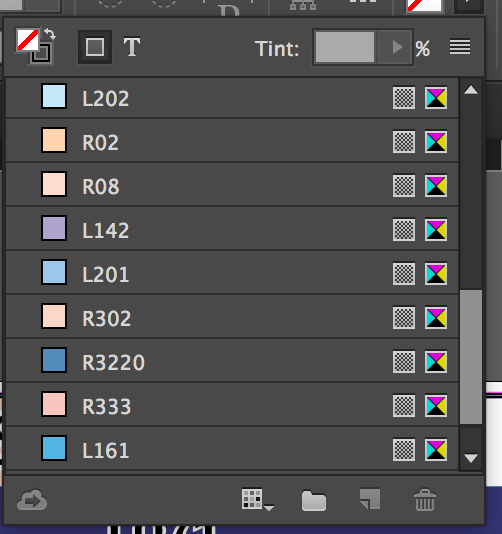

I've been using the same base InDesign file for the past few years, and with each show, I add more color swatches to the library based on the colors that I'm using in the show. These are close approximations, not exact - the goal is to quickly find systems, not to pick colors.

I need to put these in order… I know.

For template systems, I add one more layer to the system box. Many years ago I stumbled across a library of gobo images and saved them to my Dropbox - I don't remember where I found it, but it means that I can quickly find a JPG of the gobo by searching with spotlight on my computer.

For template systems, I add one more layer to the system box. Many years ago I stumbled across a library of gobo images and saved them to my Dropbox - I don't remember where I found it, but it means that I can quickly find a JPG of the gobo by searching with spotlight on my computer.

I take the image, change the opacity, and drop it in the square.

COLOR SCROLLS & MOVING LIGHTS

The moving lights themselves get put on the sheet like any other light, only I put the channel numbers where the physical fixtures are hung vs where they will be pointing - because, well, they move.

If there's room, I'll add some basic position palettes and the gobo wheels.

For scrollers, I do two different things depending on how many different scrolls are being used. If there's only one type in the show, I"ll usually just put the scroll image across the page. If there are multiple, I'll sometimes put them in the color bar of the individual system boxes, sometimes on their own sheet. It really depends on the show.

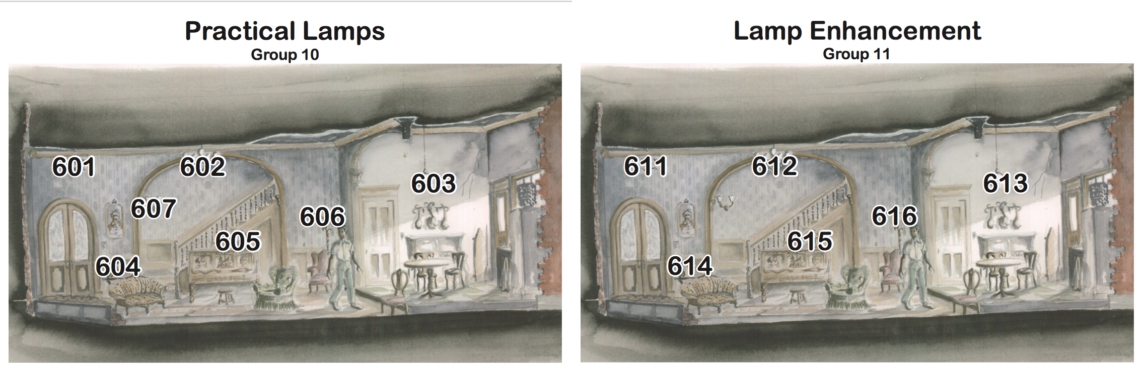

PRACTICAL LAMPS

Have a lot of practicals in your set? No problem! Take the renderings from your scenic designer and use them as a visual magic sheet!

(Below: The Piano Lesson, American Stage Theatre Company - Frank Chavez, scenic design.)

PRINTING THE MAGIC SHEET

After all this is done, I'll export the sheet to PDF and then print a few copies of it. I typically wait a day or two to go over it for errors. I almost ALWAYS forget to change some channel numbers (I copy paste.)

After all this is done, I'll export the sheet to PDF and then print a few copies of it. I typically wait a day or two to go over it for errors. I almost ALWAYS forget to change some channel numbers (I copy paste.)

Then, it's off to FedEx Office to laminate at least one of them. I print them on 11×17 Tabloid sized paper, which costs about $4 to laminate. I first did this when working out an outdoor production, but then kept doing it. It makes them really durable for tech and also allows me to have a really cool collection of laminated magic sheets.

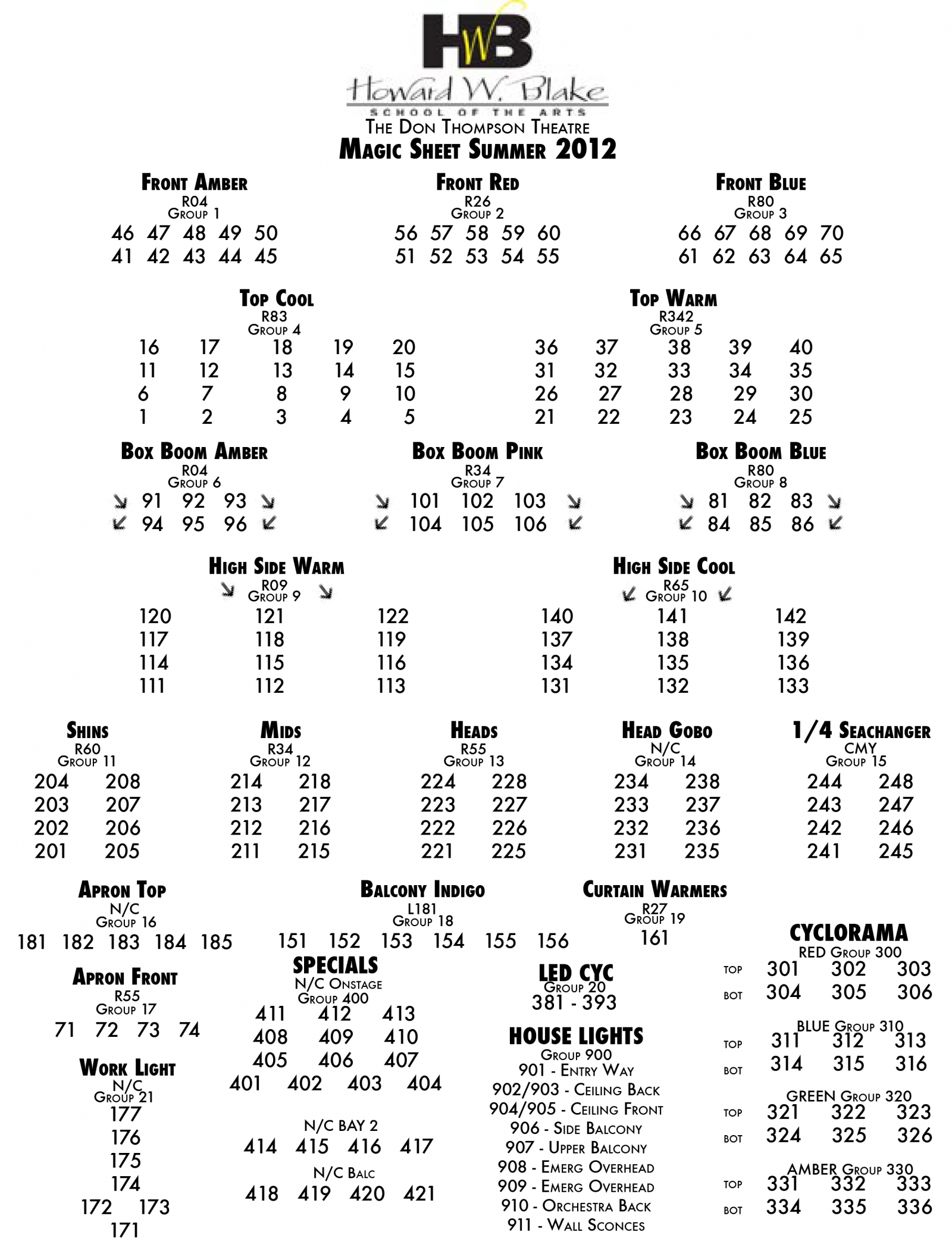

OTHER STYLES

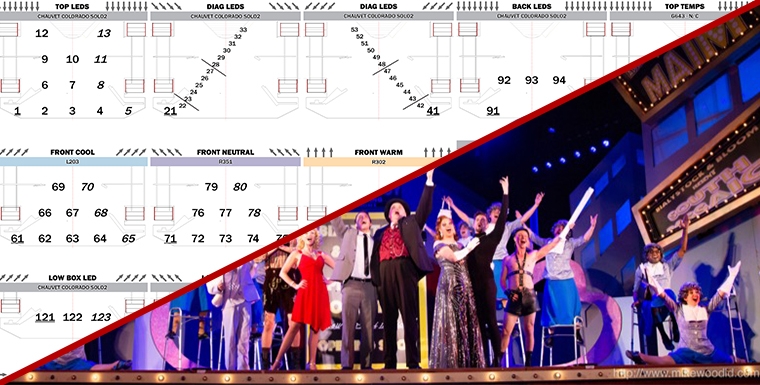

Sometimes, I need a very simple and easy to read magic sheet. One that anyone could sit down with and create a show. For this, I rely less on the graphics and colors and more on just the raw data. This typically is only for rep plots.

Sometimes, I need a very simple and easy to read magic sheet. One that anyone could sit down with and create a show. For this, I rely less on the graphics and colors and more on just the raw data. This typically is only for rep plots.

To the right is a sample of a magic sheet for the HWB School of the Arts house plot.